A View into the Rainforest

If you’ve ever stood on a quiet trail in the Hoh Rain Forest, you know the feeling: the trees seem to breathe all around you. Fog threads itself between towering Sitka spruce and western hemlock. Bigleaf maples carry shaggy coats of moss and epiphytes. Roosevelt elk — if you’re lucky enough to spot one — leave tracks in the spongey duff. This is a place where twelve—and sometimes even fourteen—feet of rain fall every year, keeping the whole system humming. Water moves everywhere, through rivulets, side channels, and downed logs that slowly transform into seedling nurseries. It’s more than just “lush.” The rainforest is an engine, cycling ocean nutrients inland through salmon and then back out again, leaf by leaf (National Park Service [NPS], 2025a).

“Then something Tookish woke up inside him, and he wished to go and see the great mountains, and hear the pine-trees and the waterfalls, and explore the caves, and wear a sword instead of a walking-stick.”

— J.R.R. Tolkien, The Hobbit (1937)

Where It Is, and Who Lives Here

Washington’s temperate rainforest stretches across the western flank of the Olympic Peninsula, especially in the valleys of the Hoh, Queets, Quinault, and Bogachiel Rivers. These landscapes fall mostly within Clallam, Jefferson, and Grays Harbor counties, overlapping the traditional territories of tribal nations who have lived here since time immemorial (Hoh Tribe, n.d.; Quinault Indian Nation, n.d.).

The forest itself is built on the backbone of its trees. Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis), western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla), Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), and western redcedar (Thuja plicata) form a massive canopy that shapes the whole ecosystem. Sword ferns and mosses take over the understory, while epiphytes climb trunks and drape branches—classic hallmarks of the Olympic rainforest (NPS, 2025a, 2025b).

Among the animals that call this place home, Roosevelt elk (Cervus canadensis roosevelti) browse the river bottoms, helping keep the understory open (NPS, 2024a). Old-growth specialists like the marbled murrelet and the northern spotted owl rely on these forests for nesting habitat (U.S. Forest Service, 2016). And of course, the smaller residents—from banana slugs inching across the trail to salmon fighting upstream—remind us that rivers and forests here are inseparable (NPS, 2025a).

Here are a few images around the beautiful Quinault Lodge.

Is the Rainforest Endangered?

Compared with Washington’s shrubsteppe, much of which has been fragmented, the Olympic temperate rainforest is relatively secure. Most of it is protected inside Olympic National Park and other nearby federal lands. Still, outside these boundaries, true old-growth rainforest is rare, existing only in patches within a larger patchwork of second-growth and working forests (NPS, 2025a; UNESCO World Heritage Centre, n.d.).

Even within the park, though, change is underway. Warming winters, shifting stream flows, and more frequent extreme weather events are already reshaping salmon runs, murrelet nesting patterns, and forest dynamics (U.S. Forest Service, 2016).

Tribal Homelands and Stewardship

The Olympic rainforest is—and has always been—the homelands of the Peninsula’s tribes. Today, stewardship continues through an eight-tribe Memorandum of Understanding with Olympic National Park, which affirms government-to-government collaboration. The Hoh, Jamestown S’Klallam, Lower Elwha Klallam, Makah, Quileute, Quinault Indian Nation, Port Gamble S’Klallam, and Skokomish tribes are all part of this co-stewardship effort (NPS, 2008).

Tribal nations are leading the way in restoration, from estuary work to river reconnection projects. These efforts weave together treaty rights, Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), and community priorities to ensure management reflects both ecological and cultural needs (NPS, 2008).

Conservation in Action

Inside Olympic National Park, old-growth stands and free-flowing headwaters are safeguarded, and their global importance is recognized by UNESCO as both a World Heritage Site and a Biosphere Reserve (UNESCO World Heritage Centre, n.d.). But conservation isn’t confined to the park. One of the most significant projects is the Upper Quinault River restoration. Tribe-led and multi-partner, this effort uses engineered log jams, floodplain forest work, and side-channel reconnections to rebuild salmon habitat and strengthen the forest’s resilience (Quinault Indian Nation, n.d.; State of Washington Salmon Recovery Portal, n.d.).

Calendar of Connection

If you’re planning a visit or just want to connect with the rainforest’s rhythms, here are a few events to consider:

- April – RainFest: A Celebration of the Arts (Forks)

A festival of readings, workshops, and cultural events that highlight the deep ties between art and place.

More info: Forks Chamber of Commerce – RainFest (Forks Chamber of Commerce, n.d.) - July – Quileute Days (La Push)

A community celebration with canoe pulls, drumming, food, and vendors, hosted by the Quileute Tribe.

More info: Quileute Nation (Quileute Tribe, n.d.) - October – Olympic Peninsula Fungi Festival (Port Angeles)

A lively event full of mushroom forays, cooking demos, science talks, and artisan vendors.

More info: Olympic Peninsula Fungi Festival (Olympic Peninsula Fungi Festival, n.d.) - Year-round – Hoh Rain Forest Ranger Programs & Trails (Olympic National Park)

Explore the Hall of Mosses and Spruce Nature Trail, or join guided ranger programs that bring the forest to life.

More info:- NPS – Visiting the Hoh Rain Forest (NPS, 2025b)

- Hoh Rain Forest Area Brochure (NPS, 2024a)

- WTA – Hall of Mosses Hike Guide (Washington Trails Association, n.d.-a)

- WTA – Spruce Nature Trail Hike (Washington Trails Association, n.d.-b)

Closing Thoughts

The Olympic temperate rainforest may feel timeless when you step into it, but it’s a landscape shaped by constant cycles of water, nutrients, and stewardship. Protected lands, tribal leadership, and community events all keep this place alive—not as a museum piece, but as a living, adapting system. And each of us has a role to play in keeping it that way.

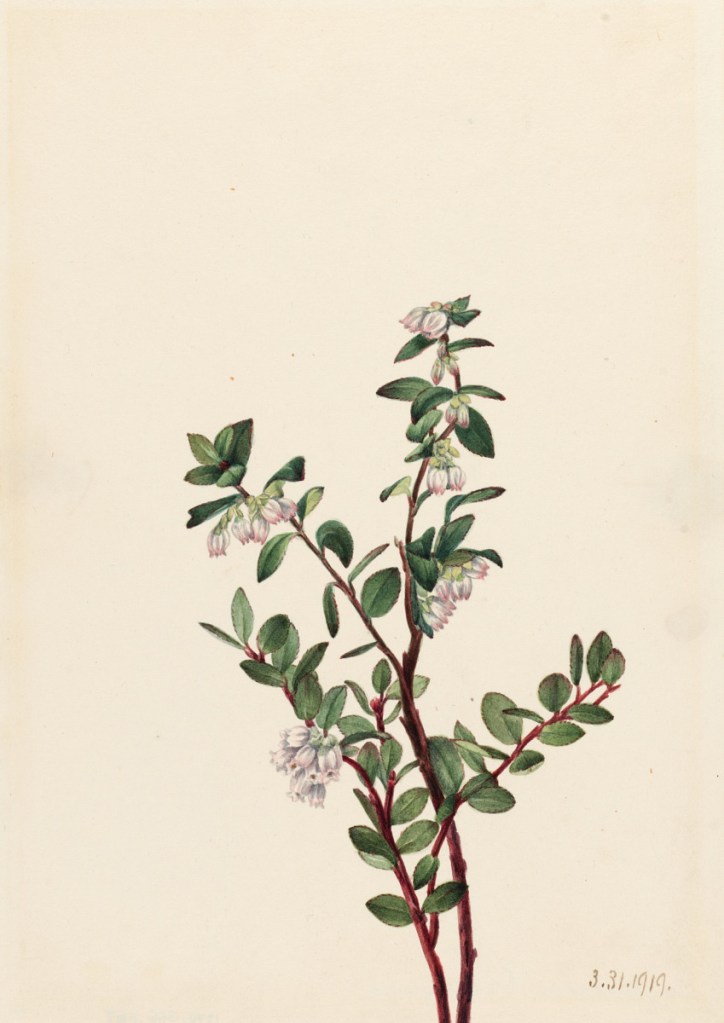

Nature Art

Mary Vaux Walcott’s watercolors capture the quiet drama of plants that define their places. While her inspirations were primarily from the Canadian Rockies, two species that she painted are indeed found in the temperate rainforest. Her painting of skunk cabbage (Lysichiton americanus) shows the broad, luminous leaves and golden spathes that glow in the dim understory—an unmistakable sign of spring in the Olympic rainforest’s wetlands and seeps. In contrast, her box huckleberry (Gaylussacia brachycera) depicts a low, evergreen shrub with delicate, urn-shaped blossoms. While the box huckleberry is native to the Appalachian region rather than Washington, Walcott’s rendering of its subtle beauty underscores the diversity of North America’s wild flora, linking distant forests through shared themes of resilience and adaptation.

References

Forks Chamber of Commerce. (n.d.). RainFest: A celebration of the arts. Retrieved August 14, 2025, from https://forkswa.com/events/rainfest/

Hoh Tribe. (n.d.). The Hoh Tribe. Retrieved August 14, 2025, from https://www.hohtribe-nsn.org/

National Park Service. (2008, July 11). Olympic Peninsula tribes, Olympic National Park sign pact [Press release]. Retrieved August 14, 2025, from https://www.nps.gov/olym/learn/news/olympic-peninsula-tribes-and-olympic-national-park-sign-pact.htm

National Park Service. (2024a). Hoh Rain Forest area brochure [Brochure]. Retrieved August 14, 2025, from https://www.nps.gov/olym/planyourvisit/hoh-rain-forest-area-brochure.htm

National Park Service. (2025a). Temperate rain forests [Web page]. Retrieved August 14, 2025, from https://www.nps.gov/olym/learn/nature/temperate-rain-forests.htm

National Park Service. (2025b). Visiting the Hoh Rain Forest [Web page]. Retrieved August 14, 2025, from https://www.nps.gov/olym/planyourvisit/visiting-the-hoh.htm

Olympic Peninsula Fungi Festival. (n.d.). Olympic Peninsula Fungi Festival. Retrieved August 14, 2025, from https://olypenfungifest.com/

Papian, N. / USFWS (2023). Marbled murrelets, a threatened species, fly over a coastal landscape in this mural painted by Lucas Thornton in Arcata, CA [Photograph]. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Public domain. Retrieved September 12, 2025, from https://www.fws.gov/media/arcatamuralcredit3norapapianusfwsjpg

Quileute Tribe. (n.d.). Quileute Days [Event page]. Retrieved August 14, 2025, from https://quileutenation.org/quileute-days/

Quinault Indian Nation. (n.d.). Quinault Indian Nation—Profile & timeline [Web page]. Retrieved August 14, 2025, from https://www.quinaultindianation.com/qin/

State of Washington Salmon Recovery Portal. (n.d.). Upper Quinault River restoration projects [Project pages]. Retrieved August 14, 2025, from https://srp.rco.wa.gov/project/110/18539

U.S. Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. (2016). Adapting to climate change at Olympic National Forest and Olympic National Park, Washington: A synthesis of climate change science to inform adaptation strategies (PNW-GTR-844). Retrieved August 14, 2025, from https://www.fs.usda.gov/pnw/pubs/pnw_gtr844.pdf

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. (n.d.). Olympic National Park. Retrieved August 14, 2025, from https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/151/

Walcott, M. V. (1919). Box Huckleberry (Gaylussacia brachycera) [Watercolor on paper]. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C., United States. https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/box-huckleberry-gaylussacia-brachycera-25900

Walcott, M. V. (1918). Skunk Cabbage (Spathyema foetida) [Watercolor on paper]. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C., United States. https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/skunk-cabbage-spathyema-foetida-26336

Washington Trails Association. (n.d.-a). Hall of Mosses [Hike guide]. Retrieved August 14, 2025, from https://www.wta.org/go-hiking/hikes/hall-of-mosses

Washington Trails Association. (n.d.-b). Spruce Nature Trail [Hike guide]. Retrieved August 14, 2025, from https://www.wta.org/go-hiking/hikes/spruce-nature-trail

You must be logged in to post a comment.